Best Authors

Elif Shafak writes for rights

Celebrated Turkish author erases all boundaries of race, age, gender, ethnicity and culture in exclusive interview.

Words are heavy in her country but that is how the internationally acclaimed novelist and widely read writer in Turkey, Elif Shafak, expresses herself best. Born in Strasbourg, France, in 1971, Shafak has 14 books to her credit already but her writing journey is just starting to pick up pace. She debuted in literature in 1994 and her first novel, Pinhan (The Sufi), was awarded the Rumi Prize for best work in mystical literature in Turkey in 1998. Her work draws on diverse cultures and attempt to break down cultural ghettoes. Her novel The Bastard of Istanbul told the story about the Armenian genocide for which she faced legal proceedings in 2006 but was ultimately dismissed off the charges.

Besides writing fiction, Shafak is an active political commentator, columnist and public speaker. She has been featured in major newspapers and periodicals, including The Guardian, The New York Times and The Independent. She has taught at various universities in Turkey, UK and USA and also writes song lyrics and scripts for television.

In this exclusive interview Shafak explores the dilemmas of writers trying to push narrative in an increasingly authoritarian and polarised Turkey and is not afraid to speak her mind.

You describe Turkish society as patriarchal, sexist and homophobic. What influence did this have on you as a female writer?

You describe Turkish society as patriarchal, sexist and homophobic. What influence did this have on you as a female writer?

In Turkey, nobody talks about the gender of a male novelist. He is regarded first and foremost a novelist. The language critics employ when they talk about a female novelist is fundamentally different from the one they use when discussing the work of a male counterpart. When you are a woman they look down upon you. It is very subtle, but very systematic. They try to remind you of your place in society and your limits. The novel, as a genre, in particular, is regarded as an intellectual work and women are not respected intellectually until they turn old. Patriarchal societies respect either de-feminised women or women in old age. So I fight back against their prejudices and deeply-rooted gender discrimination, both latent and manifest.

You spoke about the rise of nationalism in the UK and some parts of Europe. What makes you so concerned about it?

Extremism in one place breeds extremism elsewhere. I am very critical of ultra-nationalism and religious fanaticism. Both of them are based on hatred and intolerance. And so is far-right bigotry. As the Sufis said long ago, as human beings, we are all interconnected. People such as Donald Trump create more anti-Americans in the Middle East fundamentalists in the Middle East create more Islamophobes in the West. It is a vicious circle. We need to break this circle of hatred, animosity and duality. We need to find narratives based on pluralism, intelligent compassion and creative humanism.

Your stories are full of historical, geographical and political themes that emerge with topics as cross-cultural complexities, generational layering and gender issues. How can you balance all these themes?

I am a storyteller with an interdisciplinary academic background. I graduated in international relations, completed my MS in gender and women’s studies and PhD in political philosophy. So somehow all of that seeps into my novels. But I guess at the heart of everything is ‘curiosity’. I am a curious person who loves to read, read, read. I believe the human being is the microcosm of the Universe. Just like the Universe expands all the time, I, a human being, have to expand my knowledge, my mind.

In Turkey, novelists are public figures and often people criticise them for reasons that have nothing to do with their writings. How can you deal with this?

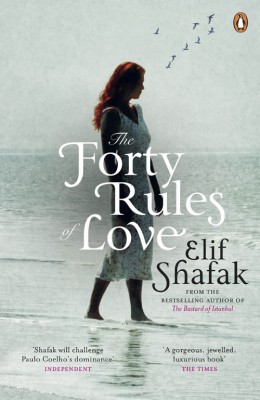

In my motherland, novelists are public figures. We easily confuse criticism with aggressiveness. Most criticism is writer-oriented rather than writing-oriented. People who have never read a book of yours can have a solid opinion about you. When I wrote The Bastard of Istanbul, I was subjected to so much hatred and reaction, especially from Turkish nationalists. There were old women burning my pictures and spitting at my photos on the streets. If you ask them whether they read the book they are reacting to, whether they read it calmly and with an open heart, most probably they will say no. But they have an opinion based on hearsay. When I wrote The Forty Rules of Love it was the opposite; I received so much love and admiration from the same people. So I learned, the hard way, not to take either love or hatred too seriously. I believe in the power of imagination, in the ancient art of storytelling, and that is a motivating force.

When one is accused of being ‘a betrayer’ and an ‘enemy of the nation’, self-censorship naturally emerges. How can writers avoid this?

Self-censorship is very widespread, but it is difficult to talk about it because it is embarrassing. Every writer, journalist, poet and academic knows that because of a book, an article, an interview or a tweet you might get into trouble. You might be lynched in social media, attacked by the president directly, prosecuted or might even end up in jail. Turkey’s rulers fail to understand that democracy is not only about the ballot box. Democracy is also rule of law, separation of powers, and yes, freedom of speech. If there is no freedom of speech, there is no democracy.

You said we have ‘no more thinkers, only storytellers’. Do you believe genuine thinkers are obsolete?

You said we have ‘no more thinkers, only storytellers’. Do you believe genuine thinkers are obsolete?

Thinkers are not extinct. However, there is a shift from ‘ideology-based social movements’ to ‘story-based political fragmentation’. This could be good or bad. It cuts both ways. One thing is clear: In the 1950s, ’60s and ’70s there was far more interest in ideologies. Today, that no longer is the case. Stories are being, unfortunately, used for bad ends as well; they are used by extremists to galvanise people. We must resist this tendency and remember that at the heart of the art of storytelling lies empathy.

You always write about strong female characters in your novels that are eager to live without social taboos? How do you relate this with the situation of women in the Middle East, Turkey and Pakistan?

I see huge similarities between Turkey and Pakistan. When I meet young Pakistani women, for instance, it is as if I am talking to young Turkish women. Our worries, our dreams, our frustrations are so alike. They are both very patriarchal lands. Patriarchy does not mean all men oppress all women; it is far more complicated than that. In patriarchal societies women also ill-treat each other. And sometimes women are biased against gay men and treat them badly. We internalise gender codes. In a patriarchal society, women cannot be happy, for sure. But young, creative men cannot be happy either. What we need is gender awareness and a sisterhood that extends across the cultural and political spectrum.

Don’t you think there is a lack of solidarity between women? How do you see women treating other women in our societies?

I am the creation of two women, in a way, namely my mother and my grandmother. They were so different from each other but there was an amazing solidarity. If it weren’t for my grandma’s support my mother could not have gone back to university as a 20-year-old divorced mom. In Turkey, it makes me sad to see that Kemalist and conservative, Kurdish and Turkish, Sunni and Alevi, working class and bourgeois women were almost never able to come together in sisterhood. The divisions in society divided them too. When women are divided into impermeable categories, it is patriarchy that benefits from the status quo.

You mentioned earlier that writers are shy from getting involved in politics. Amid what’s happening now, especially in the Middle East, can they still remain apolitical?

If you are a writer from Pakistan, Egypt, Turkey, Nigeria — places with wobbly democracies — you do not have the luxury of being apolitical. I cannot be apolitical if I care about what’s happening in the world. I come from a feminist movement. One of the best things feminism did was to explain how politics is not only confined to Parliament or political parties. Daily life, too, is political. There is politics in our homes, in our schools and on our streets. If you see politics in this way, how can a writer be apolitical?

Is there a link between your personality and characters of your novels?

I have never seen my books as autobiographical. Certainly there are echoes and similarities, but frankly, I am not interested in writing about myself. How boring that would be. I am more interested in transcending myself, going beyond the boundaries of the ‘self’ that was given to me at birth and becoming the ‘other’. When I write about the ‘other’ — ethnic minorities, sexual minorities, the persecuted voices etc — I realise I write about myself. I always felt closer to those on the periphery than to those at the centre, to those who are silenced than to those who speak aloud and to those who have been disempowered than to those in power.

Do you still think different ethnic groups, such as Armenians, Turks and Greeks, can coexist?

I am a big believer in cosmopolitanism. In this life if we are going to learn anything at all, we will learn it from people who are different from us. Diversity is a blessing. It is a beauty, if we could only see it this way. All totalitarian regimes are based on a fake notion of sameness and that is very dangerous. Where there is a culture of sameness, literature will suffer, creativity will suffer, human beings will suffer. It breaks my heart that Turkey lost its cosmopolitan heritage because of waves of nationalism, religiosity and intolerance.

In ‘The Bastard of Istanbul’ you write that Turks want to put the past behind them and start fresh. In your opinion, how can this be achieved in today’s tense and bitter Turkey?

Walk around Istanbul, even though history is so rich and vivid, it is a city of amnesia. But remembering is a responsibility. We need to remember, not in order to remain anchored in the past, but to learn from the mistakes of the past. We, Turks, need to understand the pain and sorrow of Armenians today with regards to the atrocities committed against their grandparents. We must tell them we feel their pain and mourn together, and then build a peaceful future together.

Earlier, you mentioned there are gaps between Turks for reasons related to their political background? Can literature narrow these gaps?

In the art of storytelling there is no ‘us’ versus ‘them’. There are only human beings with similar sorrows and joys, similar dreams and nightmares. Stories can and do bridge gaps — mental and cultural.

You have written over a dozen books by now. How can you ensure you do not repeat yourself?

I have 14 books now, nine of them are novels. Each and every book I wrote has been different than the previous one. This is a massive challenge for my publishers too. If a book is successful, publishers expect the author to keep writing similar things. But I have not done that. For me, every book is a new journey, a new universe and I invite the reader into this journey. And, the only way to not repeat yourself is to remain a student of life, to keep your heart and your mind open.

In which language do you think most of the time, or even dream in?

Three languages accompany me to this day: Turkish, English and Spanish. I write fiction in English, then my books are translated into Turkish and I rewrite the Turkish translation. So I write each book twice. It is insane. The only reason I do this is because I love language. I dream in more than one language. And I have always believed that if we can dream in more than one language we can write stories, novels and poetry in more than one language.

What does the future hold for books and publishing in the digital age? Has the existing model broken or only partly eroded?

I am not as terrified by digital technology as some of my writer friends. The format will change as it has always changed and evolved throughout history. What stays unchanged is our need for stories. This is an existential need. The art of storytelling is ancient and universal and will stay with us. On the other hand, I am sad to see how fewer people read novels in the Muslim world, especially men. Anyone who says “I don’t have time for novels” is essentially saying, “I don’t have time for empathy, I don’t have time to be human”. That is a dangerous alienation.

What points do you keep in mind while writing a novel, given the changing nature of reading habits?

Every writer is the child of his times, in a way. I follow the world and put thought into the things that matter to humanity. And I write the kind of stories I love to write. The great architect Sinan said, “Work is a prayer for the likes of us”. I know what he means. Writing is my prayer. I do not mean this in a religious way at all. Prayer is a connection with something beyond or bigger than yourself. Writing is my way of connecting with something beyond or bigger than myself. So writing is a secular prayer for me. I am even active on social media, Twitter basically. I am also a public speaker and I believe in the power of oral storytelling.

Do you see novels surviving another century or two?

As the world we live in becomes faster, more dizzying and ambiguous, our need for an ‘inner space’ increases. Novels speak to the inner space present inside every individual. So paradoxically, the faster we become, the more impatient we become, the more our need for in-depth stories grows.

Interviewed By Naveed Ahmad

The writer is a Pakistani investigative journalist and academic with extensive reporting experience in the Middle East and North Africa. He is based in Doha and Istanbul.